Thanks to Jeremiah for allowing me to guest blog for a couple of weeks. In my first three posts, I thought I'd briefly summarize the analysis of the Bloomberg administration's approach to urban governance that I lay out at length in my book, Bloomberg's New York: Class and Governance in the Luxury City.

What is this approach to urban governance, which I call "the Bloomberg Way," all about?

Well, it's not really about Michael Bloomberg. Or rather, it's not just about Michael Bloomberg. Often when Bloomberg's mayoralty is discussed, the focus is on the man himself: his experience, his personality, his foibles and eccentricities. But the political emergence of Michael Bloomberg and his approach to urban governance are products of a broad transformation of New York City's social structure over the past several decades: as media, financial, and business services have come to dominate the city's economy, there has emerged a "postindustrial elite," made up of high-level professionals as well as New York-based executives and owners of global businesses.

This postindustrial elite has absorbed the great part of the wealth generated in the city for the past several decades; however, until recently, it had remained largely disengaged from politics and governance. While there was the occasional financier deputy mayor, the postindustrial elite didn't offer up a coherent and sustained political project...until 2001.

As I detail in the book, Bloomberg's 2001 election drew a remarkable number and range of postindustrial elites--financiers, business consultants, academics, corporate managers, marketing executives, and so on--into City Hall. Most of them had never considered "public service" before, and many of the folks of this ilk that I spoke to said that it was the presence of Bloomberg, the CEO Mayor, that had drawn them into government. Moreover, they made it clear that they felt, as one of them put it to me, that "the city needed us." They interpreted the city's post-9/11 problems as problems of management and marketing, as technical problems looking for the "solutions" that their skills, experience, and expertise could solve. Thus, their leadership was key to the city's recovery and its long-term prosperity.

Michael Bloomberg was the most prominent of these postindustrial elites, and the one who provided the impetus for this movement into City Hall. But ultimately, this was a class mobilization, the first time the city’s postindustrial elite directly seized the reins of city government and sought to shape governance--and the city itself--in its own image.

13 comments:

Hm. Interesting

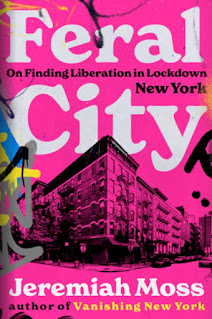

the cover photo says it all...

Bloomberg was foreshadowed by Richard Riordan, who served as mayor of Los Angeles from 1993-2001 and there are indeed many similarities, including a similar term limits issue. It would be interesting to know if Prof. Brash sees this political awakening of a post-industrial elite as something that is primarily a phenomenon limited to New York City, or whether it is part of a larger trend.

Look forward to picking this up.

am i the only one who sees this as arrogant. dont for one minute think that the "elite" of the city care one minute about the city and its citizens, they care about making their surroundings more attractive and comfortable.

The problem with Mayor Bloomberg and his crowd are that they have no idea what it's like to have to work really hard just to be able to barely exist in this city. The alternative is moving and that's something I don't want to do and I am constantly nervous and wonder where I'll be a year from now. They have no idea what that feels like.

yeah, the city "needed" them to make it over in their image. sounds a little God-like.

Reading about B'berg, I note a persistent absence of narrative re: his earlier behavior. Didn't he try to block protests against the Iraq War, the Republican Convention? A former neighbor, a cyclist, told me he liked to ride in a group event, Critical Mass. B'berg, he said, tried to block the riders, calling them potential terrorists. What's his problem with freedom of speech? With exercise? He's real elite.

Isn’t this paternalistic attitude that the corp sector knows best a bit ironic when you have a corporate executive moving into public service to then take the position that govt knows best? Either way, I’m not much of a fan of paternalism.

I lean towards being critical of policies instead of people, although to expand on Marty’s point, it’s the responsibility of govt to serve its constituents, not a select few, and some officials are better listeners than others, and significant voices are either not getting heard or being ignored. Accountability is a term that I often hear from the private sector, which I’d like to hear more of from public sector officials in a meaningful way.

A thought-provoking guest blog series. Looking forward to reading more.

drewjub: to respond to comment. yes it is world wide. all over. & worse than NYC! across the USA, all developing countries. this is a global trend. what does brash say?

my 2nd comment: there are millions of $$s being poured into NYC. off shore money. politicians take their cut. its globalization. theres a market for the condos, & stores. there is a new upper middle & wealthy class world wide.

Thanks for the comments and interest everybody. Just wanted to respond to drewjube, as s(he) brings up a point I touch on in the book. I think that the NYC case is in fact just one of many case in which postindustrial elites -- corporate executives and people from the white collar professions -- are asserting their leadership, sometimes at the urban level, other times at the national scale.

There are a bunch of examples from both the US and abroad: Riordan in LA, Paul Allen in Seattle, Tom Leppert in Dallas, Lee Myung-bak in Korea, and the late Rafik Hariri in Lebanon, for intance. Moreover, the so-called "creative class" has asserted itself in cities from Tacoma to Toledo to Providence. Finally, we have one Barack Obama, whose moderate, professionalized, and technocratic approach to politics and governance are clear expressions of his professional-managerial class background, and who seems to think, to paraphrase Doug Henwood, that our problems can be solved by getting the smartest people in the country together in one room (the anthropologist Karen Ho has a nice analysis of the whole notion of "smartness" in Liquidated, her ethnography of Wall Street).

And though it seems far in the past, we shouldn't forget that Bloomberg was propelled into office on the 1990 wave of CEO adoration; as I note in the book, along with others like Tom Frank, the rehabilitation of the image of the CEO was itself an important piece of upper-class cultural politics.

Americans of all stripes have tended to put their faith in solutions involving management, and often, as in the creation of the United Nations or World Bank this has been a good thing, or at least a thing with potential for good. Better than control by terror, secrecy, and force of arms, at any rate.

I think it was Henry Luce and his American Century who urged that business magnates ought to be the leaders of the world, official or unofficial -- they were so anointed by Providence, he felt. This has been our ideology since the fall of the New Deal -- and, I suspect, that of the CIA since the fall of the Berlin Wall. We see the results of this arrogance, beginning with McNamara and the Kennedy whiz kids.

As a resident of the boroughs I feel that to the Bloomberg administration we represent distant colony inhabited by an exotic and ignorance populace who don't know what is good for us and whose concerns don't matter.

Anyway, this looks like a fascinating book and I am eager to read it.

Post a Comment