1.

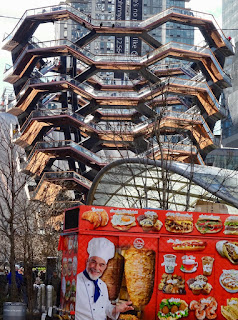

Cornelius “Neil” Byrne leans against the stall of a butterscotch horse named Cowboy and gazes out the second-story window of Central Park Carriages on far West 37th Street. Just a few blocks to the south, a crowd of construction cranes stabs the sky above Hudson Yards. They swing slowly back and forth like giant knitting needles stitching together the new mega-development from scratch.

“I keep looking out at those cranes,” Byrne says. “You don’t have to be a real estate expert to see what’s going on here. So much is going to follow those cranes. Unprecedented growth, they say.

I know why Bloomberg called this neighborhood the new Gold Coast. That’s change out there. And it’s change that’s eliminating me.”

If Mayor de Blasio’s plan to ban carriage horses goes through, Byrne and the handful of other stable owners in the city will be forced to close, their century-old buildings demolished, and their horses--about 200 of them--scattered to places no one’s exactly sure about. Behind the ban are the pleas of animal rights activists, who see the urban housing and driving of carriage horses as cruelty. But alongside the outcry, complicating the situation, there’s something more—big real estate money and the unstoppable juggernaut of

hyper-gentrification.

Roped into the Hudson Yards scheme due to their proximity to the Jacob Javits Center, properties in this area are being grabbed by the city’s most powerful players. The Chetrit Group, the same developer that took over the Chelsea Hotel,

spent $26.5 million on the old buildings next to Central Park Carriages.

Numerous reports, from Michael Gross'

initial blog post in 2009, to the

New York Times, have revealed that a major force behind the ban is de Blasio campaign supporter and real-estate magnate Steve Nislick, who founded the powerful anti-carriage group NYCLASS. With wealth gained from a chain of parking garages, he is lobbying hard to replace the horses with electric cars--he

denies that he wants the stable properties.

I walked through three of the west side stables and saw animals that were fed, cleaned, watered, and shod, with cushioned stalls big enough for turning around and lying down. Open windows on all sides of the stables let in fresh air, and the smell is that bracing, healthy aroma of manure and hay, like a brisk day on the farm. Inside, you feel like you’re in another time and place. It’s quiet here, with no traffic noise, just the soft sound of horses moving about the straw.

This is a native environment for Neil Byrne. Born in the rough heart of Hell’s Kitchen, the son of a Hansom cab driver, Byrne bought the building that houses Central Park Carriages in 1979. Today he owns a fleet of 17 horses and carriages, including his father’s 1902 Hansom, painted Brewster green and filled with memories of its days rolling through the city behind a mare named Sunshine Shannon. Hidden in the cab’s seat cushions, Bryne discovered a cache of artifacts, including a ragged souvenir photo of a long-ago dinner party at the famous

Leon and Eddie’s, the faces of the tourists washed away by time.

Byrne holds these fragile ghosts salvaged from his father’s Hansom and says, with a rueful laugh, “This is all my father left me. This cab and a lot of bills.” He remembers a childhood spent in poverty, but without self-pity. “

Look, nobody started on the top of the mountain here. We’re all guys who struggled for what we’ve got. That’s why we want to hold on to it. This is torture what they’re doing to us. There’s a lot of sleepless nights. It’s tough. Guys keep asking, ‘What’ll I do if I can’t do this?’ And they don’t come up with an answer. Me? I don’t know what I’ll do. I couldn’t even work at McDonald’s.”

2.

One block north, at West Side Livery on West 38th Street, stable manager Antonino “Tony” Salerno clicks his tongue at a black beauty named Spartacus and the horse plants an oaty kiss on the man’s cheek. Salerno is happy here and the horses appear to be happy with him. They lean out of their open wooden stalls to nuzzle him, and each other, as he walks by.

“I don’t understand,” he says. “We don’t have cruelty here. This type of horse built New York City, working together with the man, building the bridges, the whole city. Now? The horse has an easy job. I can pull the carriage myself!

They say they’re gonna rescue the horse? That’s like coming into your house and stealing your kids, saying, ‘We’re rescuing them.’ These horses are my family. They’re gonna take my kids?”

Salerno grew up with horses in his home village in Sicily, where his grandfather drove a carriage. In New York he tried life as a cabinetmaker, but “the mind is in the horse,” so he stopped cabinetmaking and went to work at the livery.

“This stable is like my house,” he says, putting a hand to his heart. “I spent 37 years in this place. If Mr. de Blasio takes my house, what I’m gonna do?

I don’t want to drive an electric car. Who wants an electric car? Some tourist is gonna get out of a cab to ride an electric car? I want to stay with the horse. The horse is alive. I know the horse. I take care of him, and he takes care of me. I spend more time with my horse than with my wife.”

There are 36 horses living here, along with one calico cat who dispenses with the mice. Real-estate developers keep badgering the owner, Mrs. Spina, to sell, but she refuses. Salerno says she’s keeping the building in memory of her late husband—and, perhaps, in memory of its long history. On the topmost floor, across a shadowy hay loft filled with golden bales, there’s a room filled with antique harnesses, horse shoes, and carriage lamps, all covered in dust and cobwebs, artifacts from the stable’s century in business, harking back to the days when the streets of New York were filled with horses. To the developers who want this property, and to the activists who want to rid the city of carriage horses, that history belongs in the dust heap of the past.

“They’re all a bunch of liars,” Salerno says, picking up a heavy U-shaped shoe, that old symbol of luck. “Just because they want to build a big building and make lots of money? Physically and mentally, they already started damaging me.

When you work and you dream, and they take it away from you, you feel like your whole life was a waste. I feel damaged because I don’t know what’s gonna be my future. My grandchildren were gonna take over, but now? I spent my life with the horse, now what I’m gonna do? I don’t have a future.”

3.

3.

Up on West 52nd Street, far from the Gold Coast of Hudson Yards, the Clinton Park Stables stands already surrounded by encroaching luxury development. As the day begins, the carriage fleet breaks out, rolling like slow-motion chariot racers into the traffic along Eleventh Avenue and branching across side streets to make the 0.9-mile trot to the park. They go past gleaming condos and high-end rentals, including yet another Avalon development, while down the street, the famed Roseland Ballroom readies for its final show, followed by demolition and a new luxury tower.

Stable owner Conor McHugh recalls when the neighborhood was “the wild west,” when the park across the way was filled with crack addicts and the streets were deserted. McHugh supports progress, but says, “We want to be a part of it. We don’t want to be run out of town. We were here when nobody was here.” McHugh got into the business of carriage driving in 1986, soon after his arrival from a small village in County Leitrim, Ireland. The county is still with him, in his green Irish-knit sweater, frayed at the elbows, and in his soft brogue.

“The job of carriage driver,” he says, “is often a starting point for immigrants. Like me. I came from a rural place, and working with horses was something I knew how to do.” The horses helped him and his fellow Irishmen get their bearings in the strange, new city.

“When we first came here, we were like wild animals. We knew nothing of the culture, of living in cities. But driving the carriage, it connected you in ways you didn’t realize at the time. It was familiar. Like home.”

With 78 horses and 39 carriages, Clinton Park Stables is the largest carriage stable in town. Originally built to house horses in 1860, it was later used as a cardboard box warehouse, and then turned back into a livery by McHugh. While it harbors remnants of its deep history—like rusted and unused nineteenth-century tie rings from the time when stalls were much smaller--this is a modern facility in many ways.

Each stall has its own water fountain, a bowl with a special spout that the horse can control by pressing with its nose whenever it wants a fresh drink. Ceiling fans are threaded with misting hoses for hot days. And many of the stalls here are larger than regulation requires.

“We feel like the good guys in all this,” says McHugh, “but that’s not how we’re portrayed. Unfortunately, the way to defeat your enemy is to demonize him.”

Stephen Malone and Christina Hansen, drivers and spokespersons for the Horse and Carriage Association, get in on the conversation.

“It’s class warfare,” says Malone, frustration in his voice. “If we were on Polo ponies out in the Hamptons, we’d be great people.”

“But we’re not cocktail party people,” adds Hansen.

4.

4.

Back on West 37th, in the shadow of the Hudson Yards cranes, Neil Byrne stands on the sidewalk, looking up at his building, remembering better days.

“It used to be we were a very welcomed part of New York,” he says. “As a driver, you were a celebrity. Now you’re a goat.” He attributes this change to Steve Nislick and the powerful efforts of NYCLASS. In a 2010 speech to a group of moneyed horse people in Wellington, Florida, a town that the

Wall Street Journal has called “

Home to billionaires with an equestrian bent” (including Georgina Bloomberg), Nislick referred to the carriage men and women of New York City as

“totally random guys” and “bad actors.” It’s a comment that sticks in the craw of every carriage person.

“

Nislick called us random people,” says Byrne. “You know what random people means? It means a guy you can just push around, not a tough guy who’s gonna fight back, not a guy with political connections. A random guy you just push out of the way. I felt very insulted to be called random. I’m not random.”

Secure in the good treatment he gives to his animals, Byrne says,

“I hope on Judgment Day that my judges are my last three horses, smoking big cigars and deciding which way I go. Heaven or Hell. I’m not worried about where they’ll send me.”

He points to the empty buildings next door, wrapped in scaffolding as they wait for the Chetrit Group to demolish them. Byrne figures that Chetrit wants his and Tony Salerno’s horses out of there, so he can acquire both stables and enlarge whatever he plans to build on the site. He also believes that Chetrit’s silent partner in the deal is the King of Morocco, but he can’t be sure. The idea is not so farfetched—Chetrit bought the Sony building last year for over a billion dollars with

backing from sovereign Middle Eastern wealth. In the air around Hudson Yards there’s enough global finance to choke a horse. And then some.

Ironically,

the cornerstone of the Hudson Yards development is the sky-high Coach tower, home of the luxury brand with a horse and carriage logo. By the time the tower rises, that logo may be the only reminder that this world ever existed.

Byrne turns and gestures toward a dusty path below the nearby overpass, to Amtrak’s Empire Line railroad cut where it runs through a large exposed outcrop of Manhattan schist. He says that’s where a pedestrian walkway will be one day, with all the air rights transferred to neighboring sites for high-rise development, just like the city did with the High Line.

Change is coming in as fast as a freight train, barreling down the tracks for the Number 7 extension.

“When that train comes,” says Byrne, “this neighborhood’s going to be in full bloom. All these people will be coming right through here. And that’s why they want my property. We’re in the way. I don’t want to leave New York. This is my New York, too."

"If things were right, if there was no eminent domain and big money and all that, I’d be in the strongest position. I could relocate. But no. They gotta screw you.

Who’s running New York? That’s what I want to know. Is de Blasio running New York, or is it Nislick?”

In January 2014, Steve Nislick responded to claims that he is interested in obtaining the real estate on which the stables stand. He stated, "No one at NYCLASS, including me, has any interest in these properties." Read his full statement here.