VANISHING

When Melva Max and her husband Jean-François Fraysse moved their restaurant La Lunchonette from the Lower East Side to the remote corner of 10th Avenue and 18th Street in far west Chelsea in 1988, it was a different world. The Meatpacking District was the domain of transgender sex workers, queer sex clubs, and meatpacking plants. The High Line was a derelict rail bed covered in weeds. Gun shots cracked through the night air. Now, 26 years later, this is one of the most expensive neighborhoods in New York City, filled with luxury chain stores and luxury high rises. The sweeping change happened recently, in the blink of an eye—and it is forcing La Lunchonette to shutter.

“The neighborhood is so gross now,” Melva says. “It’s all tourists coming for the High Line. People always say, ‘But wasn’t it great for you?’ The High Line has been the cause of my demise.”

Since the pricey park opened, Melva’s landlord’s phone hasn’t stopped ringing, and it’s always a real-estate developer on the other end. “My landlord’s not a bad guy, but how you can you say no to offers of $30 million?” He’s giving her until June 2015 and then she’s out of business.

[

A shorter version of this essay appears in today's Metro NY]

When the High Line opened its first phase in 2009, critics raved as neighboring small business people looked on uncertainly, hoping the park would be a rising tide to lift all boats. That didn’t happen. By the time the High Line’s second phase opened in 2011, small businesses in its shadow were dropping like flies (

mostly blue-collar businesses), making room for massive, high-rise development exclusively for the global super-rich.

What most New Yorkers do not know is that the luxury mega-development scheme was baked right in to the High Line preservation plan.

In the book

High Line, the park’s co-founders Joshua David and Robert Hammond explain how, in order to preserve the train trestle, the air rights above it would be sold off to developers to build a new neighborhood filled with soaring towers. David recalls saying to Hammond at the time, “If the result of doing the High Line is that you end up with all these tall buildings that you wouldn’t have had otherwise, I don’t want to be a part of it.” Gradually, however, David came around--“my perspective changed,” he wrote. As Joseph Rose, chairman of the New York City Planning Commission, told them, “The High Line had been an impediment for so many years. You and your group changed it into a catalyst.”

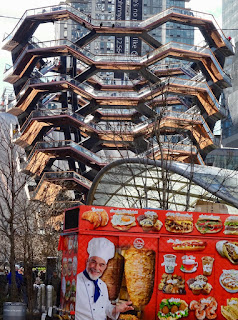

Still, what the High Line had catalyzed was unfathomable at the time. Glistening towers rising 20, 30, 40 stories into the air, pressed tightly together, casting cold shadows and blotting out the sky, all along the length of the park? Condos with their own personal swimming pools? Russian oligarchs stashing investment money in glittering vertical ghost towns? Who could believe this claustrophobic dystopian vision would ever be permitted?

In 2011, in a love letter to the High Line, Philip Lopate wrote, “Much of the High Line's present magic stems from its passing though an historic industrial cityscape roughly the same age as the viaduct, supplemented by private tenement backyards and the poetic grunge of taxi garages.

It would make a huge difference if High Line walkers were to feel trapped in a canyon of spanking new high-rise condos, providing antlike visual entertainment for one’s financial betters lolling on balconies.”

That vision has come true—and more so every day, now that the High Line’s final phase has opened, a ribbon wrapping a bow around what will be the Hudson Yards billionaire city within a city. The poetic grunge has gone with the exiled taxi garages. And the tenements, like the one containing La Lunchonette, have been pulverized to dust as new towers rise in every remaining open space.

“People aren’t going to like me for saying this,” Melva says, “but

it feels like Disneyland around here now. Everyone’s fighting the crowd to get to the next ride. People on the High Line look like lemmings, like they’re walking on a treadmill. They’re not even looking at the plants. They should sell t-shirts up there that say, ‘I Did the High Line.’”

But shouldn’t tourists be good for the local economy? Melva explains that, even though there’s a High Line staircase right outside her building, most tourists don’t come down.

“They get off their big tour bus down at Gansevoort, walk to the end of the High Line, and then the bus picks them up again. Most of them never get off the High Line.”

Those who do venture down the stairs aren’t interested in eating a meal. They’re interested in Melva’s bathroom. “People come down to use my toilet. I get 20 – 30 people a day who just want to use my toilet.” She lets pregnant women, elderly people, and children use her bathroom; the rest she turns away. “They yell at me! Like it’s my job to provide them with a toilet.”

Melva is a warm and generous person. She calls all her customers “Honey” and touches them gently on the shoulder as she quietly glides up to ask if they need anything else, more water, another glass of wine. She makes you feel welcome and well cared for. A reviewer at

New York magazine once said that

walking into La Lunchonette is “like having someone put two warm hands on your cheeks.” Those are Melva’s hands.

But she’s also angry. Her anger at the High Line, the tourists, and the hyper-gentrification that has decimated Chelsea is shared by many New Yorkers, people who are tired of their neighborhoods changing into pleasure-domes for the rich, amusement parks for tourists, Anywhere USA’s filled with suburban chain stores.

Still, Melva says, "I love the High Line," specifically the views, the sunsets, and the air, all things that are being destroyed by overdevelopment. Even the rich are starting to complain, she says, upset about tourist buses idling in front of their condos, belching black exhaust fumes into the air. Even the rich are talking of leaving.

“What people don’t understand,” Melva explains, “is that it could have been a nice park. The zoning could’ve stayed so it didn’t attract all this grotesque development. It could have been done in a more creative way. And I’d still have my business.”

She adds,

“The High Line was a Trojan horse for the real-estate people. All that glitters is not gold.”

Back in 2005, with Dan Doctoroff and Amanda Burden leading the charge, and with support from the Friends of the High Line, the Bloomberg Administration

rezoned several blocks of West Chelsea--all “with the High Line at its center,” recalled Hammond in

High Line.

In the city’s zoning resolution, they wrote out the explicit purposes of creating this special district. Aside from encouraging development and promoting the “most desirable” use of land (already in use), one purpose was “to facilitate the restoration and reuse of the High Line” as a public space, through, in part, “High Line improvement bonuses and the transfer of development rights from the High Line Transfer Corridor.” Bonuses along the corridor meant that if a luxury developer provided improvements to the High Line itself, that developer would be given permission to build their condo towers even bigger. And they did.

Another purpose of the West Chelsea rezoning, according to the city’s resolution, was to “create and provide a transition to the Hudson Yards area to the north.” In essence,

Special West Chelsea was zoned to provide a link between the glamorous Meatpacking District below and the glittering new neighborhood above, all with the High Line running through, like a conveyor belt ferrying tourists and money up and down. To the developers of Hudson Yards, Bloomberg gave millions of dollars in tax breaks, including approximately $510 million to the Related Companies.

On their marketing materials, Related calls Hudson Yards “The New Heart of New York.”

I ask Melva how she might respond to charges that her restaurant helped usher in gentrification back in 1988. She says, “I have to concede that the galleries came, in part, because we were here. But

our prices have always been fair, and our clientele is not all rich people. It’s a middle-class place, but there’s no room left for the middle class here. It’s a matter of degrees.” We talk about

gentrification versus hyper-gentrification, how today’s changes are being created by the city government in collusion with corporations.

The catastrophically rising cost of Chelsea has pushed many of La Lunchonette’s regulars out of the neighborhood. And for the newcomers who fetishize the flashy and new, La Lunchonette’s “low-key” and “divey charm,” as Zagat puts it, is not their cup of tea.

It’s really too bad because dining at La Lunchonette is an absolute pleasure—and a rare experience. The music is soft--Miles Davis, Edith Piaf--and the rooms are cozy. The food is good—I had the lamb sausages and carrot-pumpkin soup. And then there are Melva’s warm hands and her kind voice asking, “How’re you doin’ Honey?” as she refills your glass.

In a city increasingly populated with iZombies, at La Lunchonette you feel like you’ve rejoined humanity, and it feels good.

Melva hopes that by letting her customers know about the closure well ahead of time, they’ll have the chance to come say goodbye and enjoy a last meal. She hopes more people will try La Lunchonette, so she can close next spring without too much debt. She doesn’t know what she’ll do next. With crippling taxes and a draconian Health Department levying Kafkaesque citations and fines, the city makes it very hard to run a small restaurant.

“This place has been my whole life,” Melva says. “I didn’t think it would end like this. This is not the New York that I love. All my customers say the same thing. And no one’s doing anything about it.”

Previously:

Disney World on the Hudson

Brownfeld Auto

Meatpacking Before & After

J. Crew for the High Line

Special West Chelsea

Previously:

Disney World on the Hudson

Brownfeld Auto

Meatpacking Before & After

J. Crew for the High Line

Special West Chelsea