Recently, the shop moved a few blocks away. Business has dropped. This often happens when a mom and pop relocates. While relocation is publicly celebrated as a victory--against a greedy rent hike, for example--or a sign of resilience, it can actually be a death sentence. In my many years writing this blog, I've talked with several small business owners who relocate--even nearby--and then are forced to shutter in just a few years.

I asked Beth a few questions about life as a small business owner in the Village.

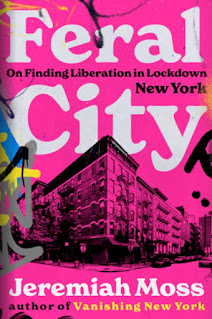

in the former location, photo via PrintMag

A: How long have you run a small business in Greenwich Village?

A: My sister Amy and I opened Greenwich Letterpress in 2005 at 39 Christopher Street in the West Village. This past March we re-located up the block to 15 Christopher Street.

Q: How have you seen the neighborhood changing and how has that impacted the small business landscape, for you and your neighbors?

A: We grew up in New Jersey, and as kids sneaking off to the city during the 90s, it wasn't because The GAP in the city was better than The GAP in Willowbrook Mall. It was because the Village/West Village had the most diverse and eclectic mix of stores.

You could start on Broadway and (affordably) shop your way back to the Christopher Street PATH station and wind up with the coolest pair of sneakers, a Smiths t-shirt, a chessboard, vintage salt and pepper shakers, an import CD, and an obscure art book. The Village was the place you visited when you wanted to escape the conventional and familiar of the suburbs. That’s why we opened the kind of shop we did in this neighborhood, to be part of that Village landscape.

Not long after we opened, we realized just how real the "boom" of Bleecker Street was and how it was trickling into the rest of the neighborhood. Where once stood small indie stores were now empty spaces sitting for years, seemingly waiting for a business that could afford $15,000 or more a month for 400 square feet. You could see the spirit of the Village vanishing.

Over the past decade we have seen beloved customers move out of the neighborhood and the city, due to rent increases. Most notably: A friend of ours talking us through the Bleecker Bob’s store closing, that she was tied closely to, and begrudgingly moving uptown. The stores we would send tourists to when they wanted to visit "other places like ours" shutting their doors. Single families (and investors) taking over brownstones that used to house several families, cutting into the actual population living in the West Village. And empty storefronts becoming a normal part of the view because asking rent was 30k+ a month. Even Barnes & Noble, Gray’s Papaya, and most recently Urban Outfitters shuttering on 6th Avenue. If those places can’t afford the Village, who can?

Q: What made you move to a new location? What's been the result of that move, in terms of business?

A: We jumped on the chance to move for several reasons. We had put an obscene amount of work into our old space over the years, even though by looking at the building you would never know it, and we couldn't continue to make improvements that we knew would only increase the value of the space for the landlord. Time and time again, we would renovate only to have our work destroyed by ongoing floods and plumbing issues that were never really addressed, as well as structural and aesthetic blemishes that were out of our reach and control to fix.

Then there is. of course, the rent--that after a decade crept up to a place that we could no longer justify paying as a small business.

We found out about a space becoming available down the street in a building with a landlord that was sympathetic to small businesses and a management company that wasn't gouging its tenants. We jumped on the rare opportunity. The move has been challenging. We sacrificed two large street-level windows into the shop for a first-floor walkup with two small windows. We got a few months out of our "we moved" posters before the listing real estate agent tore them down in the old space. We keep hearing the “sorry you closed," despite our best efforts to post that we only moved.

Q: What challenges have you faced as a small biz in the city?

A: The obvious challenge is the fact that we need to sell a huge number of products in order to simply pay our rent. This necessitates having a large and broad-based clientele visiting us daily.

Coming into a historic district over a decade ago, we certainly were aware of the desire to preserve the facade of the old Village. Unfortunately, for many small businesses, it does come at a cost. For instance, the simple act of putting a hanging sign above our business to let customers know we still exist has become a four-month process, with countless back-and-forth emails with the various building commissions (luckily we have our landlord and the building management company on our side with us).

We completely understand the desire to keep the integrity of the neighborhood, but also would like to hope that the various commissions would see the struggle of small businesses. We still are not allowed to put up a sign letting people know we are here, and this does have an impact on the number of customers we get. At the end of the day, we sometimes throw our hands up and wonder who out there do you turn to for help or understanding?

The new plight of the small business owner in New York City is that, more and more, you feel alone in this, because it's a shrinking club and the membership fees are too high.

Beth is right. Small businesses are the neglected underdog in a city that explicitly favors corporations and chains. Currently, there are no protections for small businesses--no commercial rent control, which the city enjoyed for years after World War II, no Small Business Jobs Survival Act, no ordinance to stop the spread of chain stores, no penalties for landlords who evict and then warehouse empty storefronts, creating "high-rent blight."

All of the above are possible solutions--some are being implemented in other cities--yet New York's City Hall and City Council will have none of it.

Tell them what you think.

Go to #SaveNYC and, with just a few clicks, send a letter to City Hall.